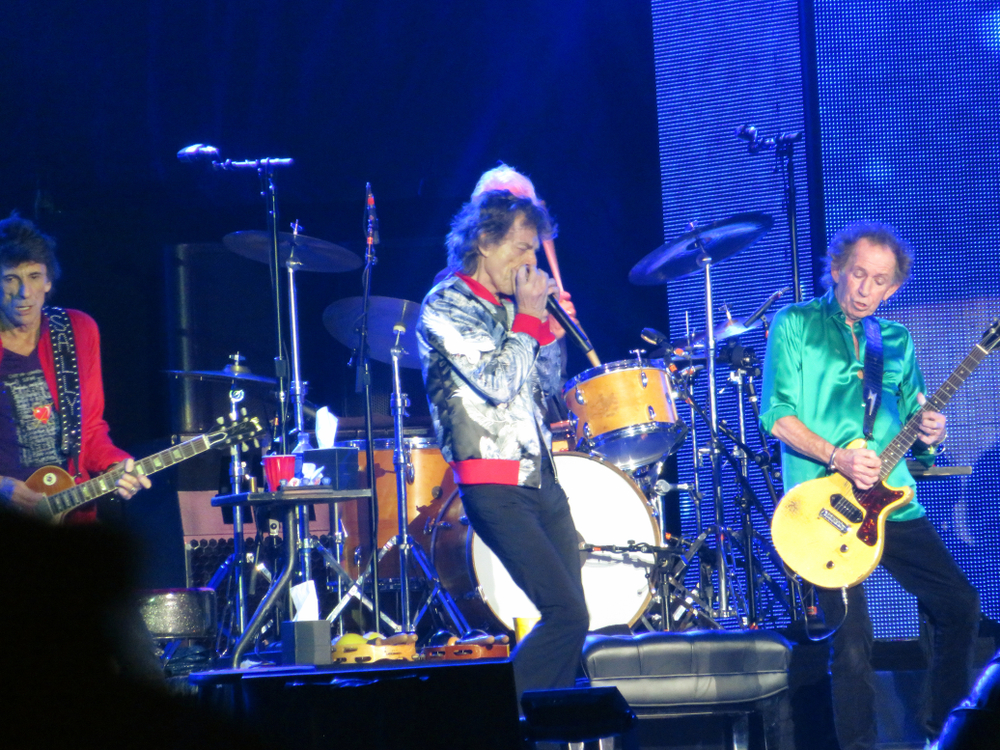

Donald Trump doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who can’t always get what he wants. But the Rolling Stones are trying hard to keep him from getting what he needs.

The music press has been full of strained Stones lyrics references like that one ever since the self-proclaimed World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band informed the reelection campaign of the 45th President of the United States that they wanted him to stop playing You Can’t Always Get What You Want (but if you try sometimes you get what you need) at his campaign rallies. The latest spin of that tune came when it played Trump off stage at his June rally in Tulsa, OK.

But the Stones aren’t alone. Twenty other musical acts have publicly complained because their music is being played at Trump campaign events. The estate of Tom Petty took to Twitter to complain about the use of his song I Won’t Back Down at the Tulsa rally. Other artists asking the Trump campaign to stop the music include Neil Young (Rockin’ in the Free World), Pharrell Williams (Happy), Elton John (Rocket Man, Tiny Dancer) and R.E.M. (It’s The End Of The World). Adweek reported this week that a campaign video Trump retweeted over the weekend has been disabled after the band Linkin Park complained its song In The End was featured in the video. The band said on Twitter that it had issued a cease and desist request about the Trump campaign’s use of its music.

But just saying ‘cease and desist’ may not be enough to stop the music being used by the Trump campaign.

Most music is copyrighted and several organizations, ASCAP (The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), BMI (Broadcast Music, Inc.) and SESAC (Society of Europeans Stage Authors and Composers), actively license that music to be played publicly. If you pay the licensing fee, you can play the music. And, as it turns out, the Trump campaign has paid to play the music.

“BMI has a specific license for political entities or organizations called the Political Entities License, which has been around for about 10 years,” explained BMI spokeswoman Jodie Thomas. “This blanket license authorizes the public performance of more than 15 million musical works in BMI’s repertoire wherever campaign events occur.”

ASCAP also licenses music to political campaigns.

RELATED: Supreme Court upholds robocall ban, but the phones keep ringing

So, the Rolling Stones can’t get no Satisfaction from the Trump campaign? Actually, the BMI license for political entities includes an option for songwriters or publishers to remove songs from the license if they don’t want the tune to be associated with a campaign, as does the ASCAP licensing agreement. And the Stones invoked that clause.

“BMI has received such an objection and sent a letter notifying the Trump campaign that the Rolling Stones’ works have been removed from the campaign license, and advising the campaign that any future use of these musical compositions will be in breach of its license agreement with BMI,” Thomas said.

The BMI letter was sent to the Trump campaign at the end of June after the Tulsa rally. The Stones and BMI are waiting to hear if Stones music is played at any future rallies. But, Thomas said, any kind of actual lawsuit over a breach of the licensing agreement is a last resort.

And, that’s the same approach BMI takes with other businesses who play music without paying the licensing fees. They try to get business to pay the fee rather than immediately take them to court.

“A BMI music license can cost as little as $378 per year — a little more than a dollar per day — depending on the size of the establishment, the type of music being played (recorded, live, DJ, karaoke), and how often that music is performed (once a week, once a month, etc.),” Thomas said. “A venue’s occupancy also factors into the cost of a license and is determined by an unbiased third party such as a fire department.”

But some businesses do end up in court. In 2015 a Tampa bar called Tadpoles ended up with a $30,000 judgment after BMI took it to court. The owner claimed the judgment put him out of business.

Tampa attorney Anthony J. Comparetto represented Tadpoles in that case. Comparetto is a musician as well as a lawyer so he sees licensing fees from both sides of the stage. If an establishment doesn’t want to pay licensing fees, they might not have live music. If they don’t have live music, musicians have no place to play and playing gigs is how most musicians make money.

“There’s always this tension between restaurants and venues that think music is free and the actual copyright holders — that’s their money, that’s their lifeblood,” Comparetto explained.

And Comparetto isn’t just talking about big name artists.

“Just because you have a hit doesn’t mean you wrote that song,’’ he said. “There’s huge amounts of people across the country who write songs, license those songs and expect to be paid on those songs. The famous one is the old Johnny Carson theme song from the Tonight Show. The actual person who wrote that was paid, I think, $440 each time it was played. He got paid that performance royalty every night they performed it.”

But, Comparetto said, it’s hard to convince small business owners they really need to pay a few more bills.

“Most venues think that music is free and think if an actual band comes in there they don’t have an actual obligation,” he explained. “A band comes in there and plays all original music, no. A band comes in there and is a Bruce Springsteen tribute band then definitely you’re going to be covered under one of the three (ASCAP, BMI or SESAC). No one wants to pay and all the musicians want to get paid.”

But, Comparetto said, it’s best for businesses to pay the licensing fees.

“You don’t want to get into a copyright lawsuit,” he said. ”The attorney’s fees on these things can be staggering. You don’t want to take these things to the max. You want to get out as soon as you can.”

While Comparetto sympathizes with bill-laden businesses, he said these licensing fees are what keep the music business going.

“I would not go ahead and go into a restaurant and eat food and not pay for it. Food is not free. We all understand that,” Comparetto said. “Again, it’s a hard thing. They don’t see it. They just imagine that these stars are the top stars and they have $100 million and you’re giving them more money. When no, there’s a whole industry that’s supported. And even though the little guy who wrote the song just gets his $150 when it’s performed, that’s what keeps him writing these songs.”