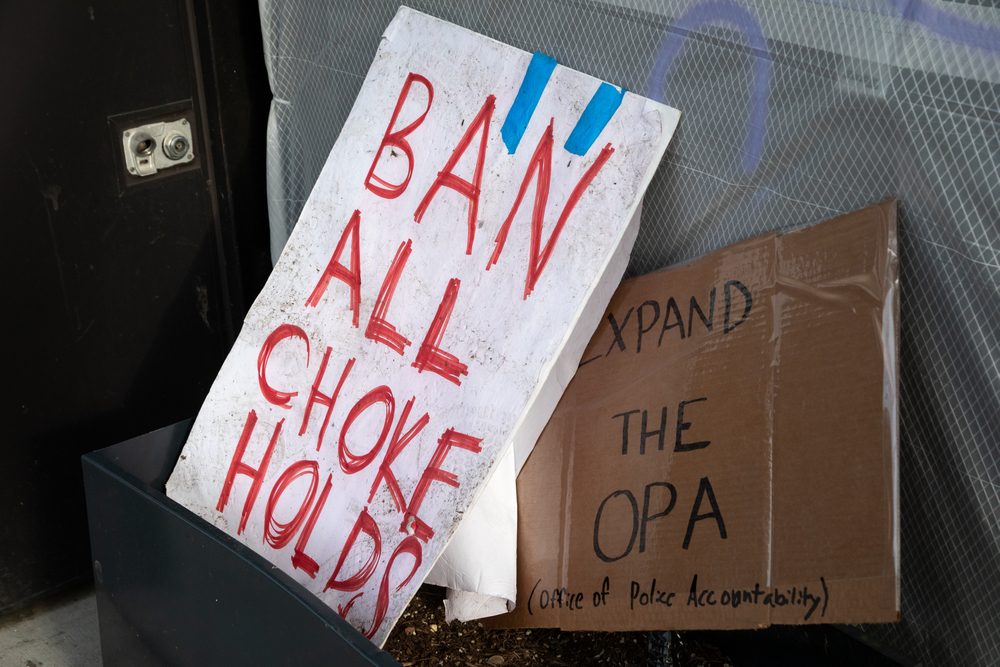

Fewer police departments are allowing the use of chokeholds since the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in May. But the practice is continuing in numerous locations. Meanwhile, families affected by the use of this method of subduing suspects are still seeking justice in cases where it has led to the death of a loved one. And protesters are still on the streets calling for police reform that would reduce the use of deadly force.

The problem with simply calling for a ban on chokeholds or allowing them only under certain circumstances is that much discretion is left to the cops, said John Raphling, senior researcher for Human Rights Watch in Los Angeles.

“It would be smart to ban the use of chokeholds,’’ he said, “and obviously there needs to be accountability mechanisms less reliant on the police to investigate themselves. There needs to be oversight that is not coming from the police departments, but generally that is not the case.”

RELATED: Police interviews, social distancing call for creativity

RELATED: Black, deaf Americans face extra obstacles when dealing with police

Chokeholds are highly dangerous and overused, he said, and there should be some regulation around that. Still it gets used.

“Just the mere fact of banning them or classifying them as deadly force, so they can only use them when there is a threat of serious bodily injury isn’t enough,” Raphling said. Because the decision on when to use chokeholds is subjective and made on the spur of the moment, it is difficult to second-guess.

“The bigger view is that we need to limit the use of police,” Raphling said. “The more things they are doing, the more likely we are going to have violent encounters because force is their main tool. What we do about it is get police out of a lot of the areas they are involved in and do things to promote public safety through support services and economic development. ...Let’s shrink their role.”

Even some within the ranks of law enforcement speak to that concept, Raphling said.

“They will say they shouldn’t be handling mental health calls because the mode of policing is not conducive to helping a person in crisis,’’ he said. “I would take that a step further to say we need to build up real services and support for people before they are in crisis. That would reduce the need to bring out police.”

An NPR review of bans on neck restraints found them largely ineffective due to lax enforcement.

“And when chokeholds specifically were banned, a variation on the neck restraint was often permitted instead.”

A chokehold restricts the airway when pressure is applied to the front of the neck. A stranglehold restricts blood flow to the brain when pressure is applied to the sides of the neck.

"The bottom line is that you're cutting off somebody's air supply (or) the blood flow to their brain and eventually they will be incapacitated," Lorenzo Boyd, director of the Center for Advanced Policing at the University of New Haven told NPR.

Michael Schlosser, director of the University of Illinois’ Police Training Institute, does not necessarily agree that chokeholds should be banned.

“With the proper training and the proper continued training, I think it is a safe method to control somebody,” he told NPR. His academy trains some 800 police agencies throughout Illinois. Schlosser could not be reached by The Legal Examiner for further comment

But in the NPR piece, he did emphasize that training must be ongoing so officers know how much pressure to give when using a chokehold in a non-lethal manner. Physical skills training, though, he said, often gets set aside due to lack of funding.

Paul Butler, a Georgetown University professor and former federal prosecutor, is author of the book, Chokehold: Policing Black Men. Butler said part of the problem with chokehold bans is a lack of accountability.

"If we look at the ban in New York City, it's kind of like a rule in an employee handbook: 'Don't use a chokehold.' We shouldn't expect those kinds of light bans to work," he said in the NPR article.

Despite a ban in place for decades, the New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board in 2014 unearthed hundreds of complaints each year against officers for using the now-controversial technique.

But even if the ban of chokeholds does not lead to more prosecutions, it could lead to better outcomes, one board member said.

Family sues in death of son

In the case of Elijah McClain, the 23-year-old Black man in Aurora, CO who became the victim of deadly force, there was not even a crime to accuse him of. Police tackled him as he walked home from a convenience store because someone had called 911 reporting a man walking down the street looking “sketchy.”

McClain’s parents are suing the Aurora Police Department, the city of Aurora and paramedics in federal court.

The lawsuit also names as defendants numerous Aurora police officers, a paramedic and the Aurora Fire Department’s medical director.

McClain, a massage therapist, was walking home from a convenience store on Aug. 24, 2019 when police approached him after 911 operators received a call of a “sketchy” man walking down the street. He was not suspected in any crime.

The 106-page civil rights complaint describes McClain as a professional massage therapist, a gentle soul, an animal lover and a self-taught violinist.

"McClain was walking back from a convenience store, where he had purchased iced tea, on Aug. 24, 2019, when officers attempted to take him into custody, pinning him down for 18 minutes — 15 of those minutes he was handcuffed,” according to the complaint.

" 'My name is Elijah McClain. That's all. That's what I was doing. I was just going home. I'm an introvert and I'm different,' a sobbing McClain said to police as they pinned him to the ground,” according to the complaint. ”'I'm just different. I'm just different, that's all. That's all I was doing. I'm so sorry. I have no gun. I don't do that stuff. I don't do any fighting. Why were you attacking me? I don't do guns. I don't even kill flies. I don't eat meat. ... I am a vegetarian.'"

McClain became unresponsive after police put him twice in a chokehold and a paramedic injected him with ketamine. He suffered cardiac arrest and died six days after the confrontation.

His last words have become chants for protests this summer which began after George Floyd died, the flashpoint for protesters demanding police reform.

Three separate investigations into McClain's death are now underway: by the federal government, state attorney general's office and the city of Aurora.

Three Aurora police officers were fired in June after photos surfaced in which officers posed near a memorial for McClain, imitating the chokehold used on him. Three officers involved in that incident are among those named in the civil rights suit.

The Aurora Police Department did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

Many advocates believe banning chokeholds will deter police violence. The idea is gaining traction. Democrats in Congress have proposed legislation that calls for a ban on all neck restraints. President Donald Trump stopped short of full support of a ban, saying only that police should avoid using it.

Move toward bans

CNN, in June, released an article looking at places where the chokehold has been banned.

“The technique has been a subject of controversy for years, particularly following the death of Eric Garner in 2014 after a police officer was accused of choking him,” the article says.

- An executive order now prohibits Connecticut State Police from using chokeholds. It requires the state's Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection to update a state police manual to “require troopers to, when possible, de-escalate situations, provide a verbal warning and exhaust ‘all other reasonable alternatives’ before resorting to deadly force.”

- The Broward County (Florida) Sheriff's Office says it will not use chokeholds to restrain or secure any person except in situations where deadly force is justified.

- In Miami, police officers are prohibited from using the chokehold, or any other restraint that restricts free movement of the neck or head or restricts a person’s ability to breathe.

- New York lawmakers passed legislation banning the use of chokeholds by officers. Known as the Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act, the bill creates a new crime of aggravated strangulation, punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

- Austin, TX, Police Chief Brian Manley announced a series of measures after discussions with a local activist organization. His department never taught or approved chokeholds, but their ban will be written into policy.

- The Chicago Police Department announced in February that "carotid artery restraints," chokeholds and "any other maneuvers for applying direct pressure on a windpipe or airway” would be classified as a deadly force technique.

- The Denver Police Department recently announced it was banning chokeholds and carotid compressions "with no exceptions."

- Houston and Washington, D.C. have also banned the use of chokeholds.