The recent ruling by District Judge Peter Cahill to hold a separate trial for Derek Chauvin, the ranking Minneapolis police officer charged in George Floyd’s death, may make a subsequent trial more favorable for the other three officers involved. The move, a reversal from an early ruling by Cahill, also removes a potential claim of an unfair trial that could have been grounds for an appeal.

In November, Cahill denied motions for separate trials from the officers’ various attorneys, who said antagonistic defenses could jeopardize the clients’ rights to a fair trial. The judge reversed the ruling last week, however, citing the inability to safely socially distance in a crowded courtroom during COVID-19, rather than a concern that the defendants will be pointing the finger at each other.

RELATED: Trying the George Floyd case is no simple matter

RELATED: The George Floyd Case: The charges, the burden of proof and sentencing guidelines

No matter the reason, Chauvin’s trial is scheduled to begin March 8. The former officer is charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter. The other three defendants’ trial will begin Aug. 23. J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas K. Lane and Tou Thao are charged with aiding and abetting murder.

Antagonistic defense

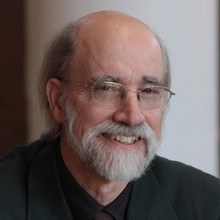

“It generally hurts the defendants to be tried together because of the guilty-by-association factor. Putting them all together would have been disadvantageous, particularly to the accomplices,” said Professor Richard Frase, criminal law professor from the University of Minnesota Law School. “When you try them all together and you bring out in greater detail than you would in separate trials all the things they were each doing. It underscores the prosecutor’s positions that the police had complete control over the situation and the suspect.”

The defenses among the three observing officers have more in common than that of Chauvin, so it makes sense to separate him, according to Ron Wright, a professor at Wake Forest University School of Law in Winston-Salem, NC, and a former trial attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice who researches prosecutors and criminal procedure.

“A trial can get reversed on appeal if a judge forces the defendants to go to trial and the defenses hurt each other too badly,” he said.

Chauvin could still plead

Though the court date is set, and jury summons have gone out for Chauvin’s trial, he could still try to negotiate a plea deal.

“I don’t think it’s ever out of the question. Sometimes the plea agreement will happen right on the eve of the trial,” Wright said. “The attorneys for the officers have to know that juries often sympathize with police officers in these cases. They are very difficult for the prosecution to win.”

If the prosecution thinks there is a possibility the jury could reach an acquittal, then negotiating for a lesser charge or the same charges but less prison time is probably still on the table, he added.

Frase also believes a plea is still possible but thinks there is little chance Chauvin will get an acquittal.

“The most I could see (the prosecution) saying ‘If you plead guilty to felony murder and save all the witnesses the trauma of going through this, we will not formally ask the judge depart from sentencing guidelines’” for more prison time, he said. Even if the prosecution doesn’t ask for a departure from standard sentencing guidelines, however, it doesn’t mean the judge won’t add prison time on his own.

Frase agrees with Wright, that historically and statistically, police officers are acquitted on murder and manslaughter charges far more than they are convicted. But he believes the case against the officers involved in Floyd’s death is far different than most. In typical cases, it is usually easy to prove the officers caused the death, but they can justify it by saying they did so in self-defense or to control an explosive situation.

“If there is a trial, I predict he would be found guilty,” Frase said. “In this case, there is no panic claim, no self-defense claim and they were completely in control of the situation.”

Safety of the jury

High profile cases with strong feelings on either side prompt safety concerns for a jury. But now, more than any time in history perhaps, extreme reactions could be triggered by an acquittal or conviction in Chauvin’s trial, as well as the number of years he is sentenced to.

The jury members will be sequestered at home and meet at a secret location to be taken to the courthouse together under protection.

“That’s a new one to me. I've never heard of that, but it seems prudent to me,” Wright said. If the jurors stayed in secure hotel rooms, it seems that would further ensure their safety as well as minimize the opportunities for jury members to read, watch or hear information and opinions about the trial.

“It’s expensive to house everyone in a hotel room,” Wright said. He added that this is no longer the norm in high profile cases as it was 30 years ago for the O.J. Simpson trial, for example.

“It is very rare. It’s really inconvenient for the jurors and it's very expensive for their local government to pay for the lodging. Most of the time, the judges believe (jurors) will listen to them when they say: ‘Don’t consume news.’’’

Still, he said this case has so much publicity and with the emotions of the country running high, he wouldn’t be surprised if the judge ultimately sequesters the jury in a hotel.

“(Sequestering in a hotel) is made more complicated by the virus because people don’t want to spend all their time around strangers for an extended period of time,” Frase said. “The courts probably have various ways to smuggle the jury into and out of the courthouse without being seen. They can block off streets to prevent the van (transporting them) from being followed.”

Contact Katherine Snow Smith at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @snowsmith.