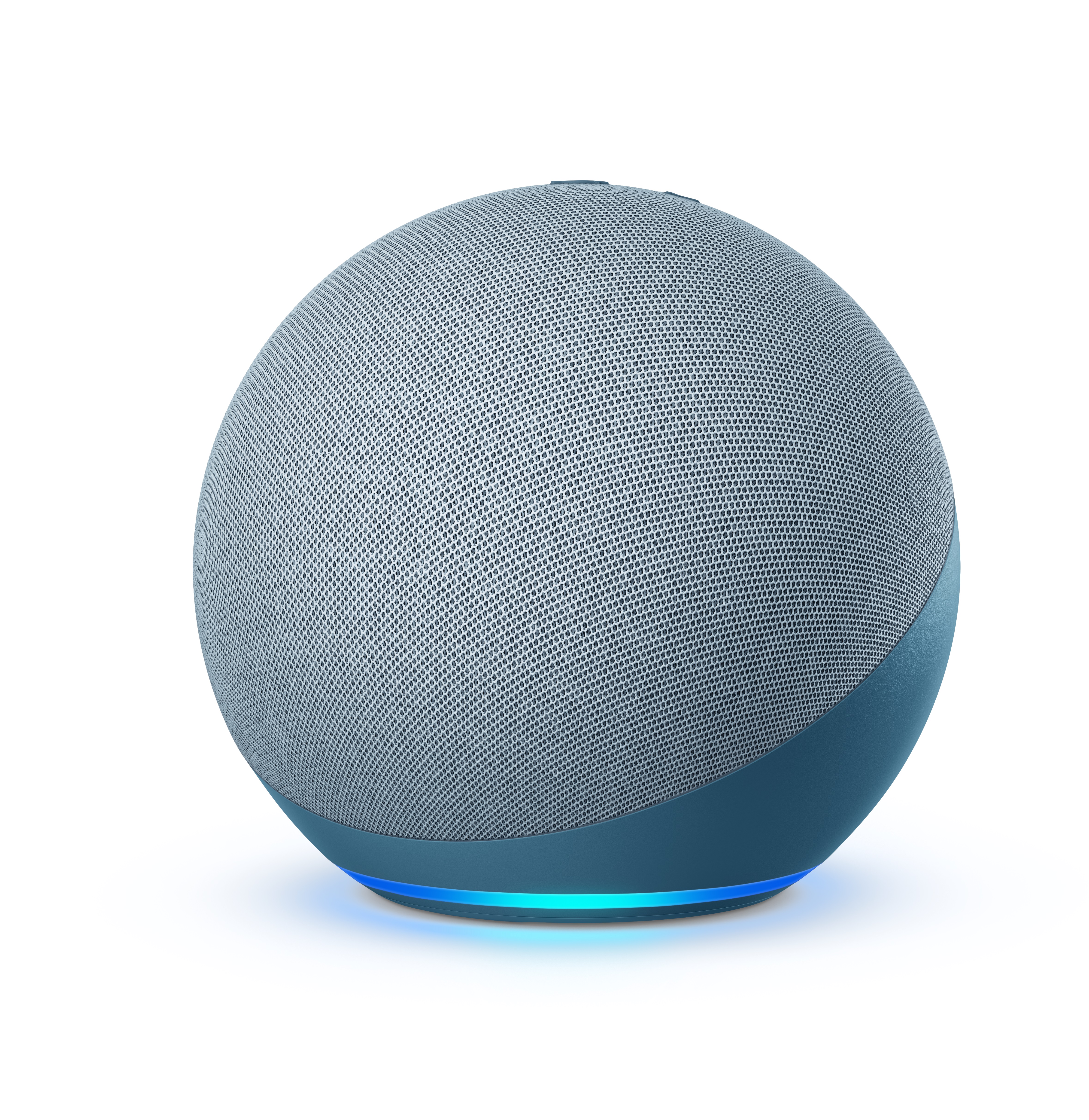

Amazon made headlines four years ago when it tried to quash a subpoena seeking recordings from an Amazon Echo as potential evidence in an Arkansas murder case. It was one of the first cases involving smart speaker recordings as potential evidence.

After the technology giant argued for three months that the information on its product was protected under the First Amendment, it ultimately provided the data when the individual who was potentially recorded gave his permission. (A judge later dismissed the murder charge.)

Since then, the number of requests from law enforcement for recordings on smart speakers has been steadily growing.

From January to June, Amazon received 2,416 subpoenas and 543 search warrants. It offered a full or partial response to 1,699 subpoenas and no response to 717. The company made a full or partial response to 430 search warrants and did not reply to 113.

Comparatively, for the same period in 2016, Amazon received 1,460 subpoenas and 221 search warrants. It made a full or partial response to 1,053 subpoenas and didn’t respond to 407. It offered a full or partial response to 175 search warrants and didn’t respond to 46.

RELATED: Macy’s being sued over facial recognition software

RELATED: Can the police search your smartphone, or force you to unlock it?

While law enforcement is requesting data from smart speakers more each year, some people may be surprised to realize it’s the speakers’ manufacturers that own the data, not the individuals who own the speakers.

“When you purchase some of these devices whether it’s Amazon Echo or Google Home or whatever, you get their privacy policy,” said Chad McCoy, an attorney with an interest in technology at McCoy, Hiestand & Smith, PLC in Kentucky. He’s also a state legislator and member of the Legal Examiner affiliate network. “Most of us don’t pay any attention at all. You just say, ‘I’ve read your terms and I agree.’ And then you’re giving them the right to do all kinds of things.”

There are ways of deleting recordings before they end up on the cloud in most cases.

“We keep voice recordings until a customer chooses to delete them. Customers can choose to have their voice recordings older than three or 18 months automatically deleted on an ongoing basis,” said Faith Eischen, spokeswoman for Seattle-based Amazon.

"Customers can also delete their voice recordings at any time in the Alexa App or on the Privacy Settings Page. More information on the ways customers can manage their voice recordings can be found on the Alexa Privacy Hub, ” she added.

Requests for interviews with Microsoft and Google were not returned.

A new frontier

Seeking data from laptops and cell phones at a crime scene has been almost as automatic as dusting for fingerprints for decades. Now, smart home devices are steadily becoming a key part of detective work as well, according to Peter Massey, Coordinator of Forensic Studies and the Justice Program at the University of South Florida’s department of criminology. With 20 years’ experience as a police officer, Massey also does law enforcement training not related to the university.

“Technology at crime scenes is my niche,” he said. “I explain to the officers all these things that are out there.”

Along with smart speakers, there are many devices that can offer pertinent information including thermostats, security systems, and the “infotainment” system within a vehicle.

“Alexa: what constitutes probable cause?”

Both search warrants and subpoenas are used to gather content from smart speaker manufacturers such as Amazon.

Typically, police or attorneys must issue a subpoena to gather information or testimony from parties not related directly to a case.

To get a search warrant, a judge must agree that there is probable cause. Massey said it’s usually not difficult to show probable cause based on direct observations by an officer or an informant that there is reasonable suspicion certain potential evidence could help solve a crime.

“Each state is going to be different in building probable cause,” he added.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, they seem to be wary of a request for a smart speaker’s recordings if there isn’t a specific reason the data could hold clues in the case.

“We have repeatedly challenged government demands for customer information that we believed were overbroad, winning decisions that have helped to set the legal standards for protecting customer speech and privacy interests,” Amazon said in a statement regarding requests for information related to its products or services.

A time stamp

“One of the toughest things to do in law enforcement is to corroborate the alibi,” Massey said. “These voice-controlled devices can offer a time stamp. For example, you can ask ‘Alexa, what time is it?’ That’s a permanent recording of where you were at that time.”

Of course, it doesn’t have to be a recorded exchange about time. Requesting a song, asking for a thermostat adjustment or turning an alarm system off, can mark a person’s whereabouts, too.

Overheard conversations

Law enforcement believed there could be arguing, or the sounds of murder recorded on an Amazon Echo and Echo Dot in home where Silvia Galva died in 2019 in Hallandale Beach, FL.

“It is believed that evidence of crimes, audio recordings capturing the attack on victim Silvia Crespo that occurred in the main bedroom ... may be found on the server maintained by or for Amazon,” police wrote in their probable cause statement seeking the search warrant, according to numerous news reports.

Still, it’s hard for a user or investigator to know exactly what’s recorded on a smart speaker’s clouds.

Though Alexa doesn’t constantly interact with its users, the device is always listening so it can answer questions or facilitate requests when a user “wakes” it, Massey said.

One would think, however, that someone arguing with his or her spouse before murdering them would have the sense to erase any potential recordings before they are stored on the manufacturer’s cloud.

“Just like not all police know to go searching for these devices, not everyone being recorded knows it could be used against them,” Massey said. “There is a lot of crime being committed by the average person and they aren’t

aware of the investigative tools at hand to law enforcement.”

Just as smart speaker conversations can be used as evidence, so can requests for information.

Remember when law enforcement reviewed the computer of Casey Anthony, the Florida mother suspected of killing her missing daughter? They found she had searched the Internet for the following: how to make chloroform, internal bleeding, neck breaking and foolproof suffocation.

Massey, going back to his point that many criminals don’t realize what can be tracked, believes people may be doing the same type of incriminating searches by a voice request to a smart speaker.

What lies ahead?

In 2018, the European Union passed a new law regarding data privacy, called the General Data Protection Regulation. It basically requires more openness from tech companies about what data they have and how they share it.

“Seeing that on the horizon, a lot of major technology companies are trying to do some self-regulation,” McCoy said.

California’s Consumer Privacy Act went into effect Jan. 1 and the state started enforcing it July 1 after a six-month grace period.

The law is similar to the 2018 EU law, in that it mandates consumers have the right to know what personal information is being collected from them and that they have a clear way to delete the data or opt-out of collection.

Companies must have a consent banner on their website that makes customers aware that their information is being collected and, again, shows a way to opt out of such collection. It also requires companies to create an easy way for consumers to know what information has been collected.

Contact Katherine Snow Smith at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @snowsmith.